By Kyle Thede, former SC&A intern and recent graduate of the Wright State University Public History program.

Iconic as they remain – and rightfully so – the Wrights were far from the only experimenters in the fledgling field of turn-of-the-century aviation. The most prominent of their contemporaries, and most bitter of competitors, was airplane designer and pilot Glenn Curtiss of upstate New York, who over the course of a decade racked up several of the most important “firsts” in the new world of aviation pioneering, not the least of which could be found in naval aviation. A former bicycle man, just like his future rivals, Curtiss had turned his focus to motorcycles in 1901, even capturing more than one land speed world record before his engineering acumen drew the attention of Alexander Graham Bell, he of telephone-inventing fame. Having already built an engine for dirigible pilot Tom Baldwin, Curtiss joined Bell’s Aerial Experiment Association as Director of Experiments in 1907.

Designing several aircraft for the AEA, Curtiss’ first less-than-fruitful attempt with flying off of water came in 1908, though it wasn’t until three years later that he succeeded in becoming America’s first seaplane pilot in San Diego, California. Enthused, the United States Navy quickly drew up specifications for a flying boat, which Curtiss spent the next couple of years designing and testing. From the private sector, department-store magnate and investor Rodman Wanamaker lobbied the Navy to employ the Curtiss craft “in the cause of science and the interest of world peace,” and so plans were drawn up that the America – as the new flying boat was named in the spring of 1914 – should attempt to make an expeditionary flight to the Azores archipelago, with Lieutenant J.C. Porte of the British Admiralty as pilot.

Porte, however, would make a hasty return to England in late summer with the outbreak of the Great War. The humanistic and exploratory plans for the America put on hold, Rear Admiral David Watson Taylor redirected the Navy’s focus on flying boats towards anti-submarine patrol work, foreshadowing the type’s preeminent role in that capacity in the Second World War. Driven by this military pursuit, Navy engineers and Curtiss designers collaborated extensively over the course of the war to improve their design, strengthening the hull and increasing the engine power until the resulting flying boat, the NC-1, stood as one of the most powerful and impressive flying machines in the world at the time of its first flight in 1918. By this time, the war in Europe had ended, and the immediate need for a military flying boat was consequently relaxed. Nevertheless, “if there is to be no fight, there will at least be a flight!” And so began the first great “monumental undertaking” of flying boats – the first crossing of the Atlantic Ocean by air.

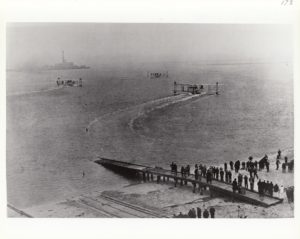

Though three Curtiss craft – the NC-1 and two sisters, the NC-3 and NC-4 – would begin the transatlantic flight from New York City on May 8, 1919 (with the assistance of government weather services, Navy destroyers, and extensive radio infrastructure), only the NC-4 would complete the voyage to Lisbon, Portugal nineteen days later. Though the flying boats themselves proved to be sturdy and capable machines, weather over the ocean was rarely favorable, or even forgiving. Approaching the Azores on May 17 – the original destination planned for the America – both the NC-1 and NC-3 were forced to make emergency landings in rough seawater following an encounter with heavy, blinding fog. NC-1 would sink three days later, while being towed by the rescue ship SS Ionia, while the crew of the NC-3 taxied their battered vessel close to 200 miles over the open ocean before they reached a Navy ship to take them aboard.

Fortunately, and much to the crew’s great relief, the remainder of the NC-4’s trek to Lisbon was uneventful, and the continuation to Plymouth, England on May 31 marked the first time an airplane had traveled between the United States and both mainland Europe and Great Britain. The symbolic significance of an American crew landing their boat at the same port from which the Mayflower pilgrims had embarked nearly three centuries prior was not lost on contemporary viewers. The voyage of the NC-4, however, would not enjoy so prestigious a place in the annals of history. Less than a month later, British aviators John Alcock and Arthur Brown completed the first non-stop transatlantic flight in a repurposed Vickers bomber. Because they completed the journey in under 72 consecutive hours, and only used one airplane, Alcock and Brown were able to collect on a Daily Mail-sponsored prize of £10,000, earning them much wider exposure and admiration than the crew of the Curtiss craft. Still, these qualifying technicalities aside, the first ever linkage of two continents by air will forever remain the achievement of that strange hybrid of a vehicle, the flying boat.

- NC-1, NC-3, and NC-4 (MS-376)

- NC-4 (MS-376)

- NC-4 in Lisbon Harbor with USS Shawmut (MS-376)

- NC-4 in Flight (MS-376)

Bibliography:

Duval, G.R. American Flying Boats. London: H.E. Warne Ltd, 1974.

The Flight Across the Atlantic. New York City: Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company, 1919.